No products in the cart.

The Evolution of Bread: From Ancient Egypt to Modern Bakeries

Imagine a world without bread—a staple that has shaped diets, cultures, and economies for millennia.

Throughout history, bread has nourished civilizations, shaped economies, and carried profound cultural and religious significance. From the flatbreads of Ancient Egypt to the artisanal sourdough renaissance, each loaf tells a story of human ingenuity and adaptation.

At Palette Synthi™, we celebrate the artistry of food and its connection to culture. Join us as we trace the extraordinary journey of bread—from its earliest origins to its modern-day reinvention.

Ancient Egypt: The Birthplace of Leavened Bread

Bread’s history begins in the fertile Nile Valley over 6,000 years ago, where Egyptians discovered the transformative power of fermentation.

Ancient Egyptian Breadmaking – A Tribute to Itjer – This 4th Dynasty (c. 2500 BCE) stele from the tomb of Itjer at Giza depicts scenes of bread production in ancient Egypt. As one of the earliest civilizations to master leavening, Egyptians transformed simple grains into daily sustenance and religious offerings, shaping the foundations of modern baking.

The Accidental Discovery That Changed Baking Forever

Egyptian bakers observed that when left in the sun, dough naturally rose, producing a lighter, airier texture. This discovery gave rise to leavened bread, revolutionizing baking techniques across the ancient world.

Bread was central to Egyptian life—depicted in hieroglyphics, offered in temples, and even placed in tombs for the afterlife. Baking became an advanced craft, refining techniques that still inspire modern bakers today.

Early Baking Techniques

- Grinding Stones → Used to mill grain into coarse, nutrient-rich flour.

- Wooden Paddles → Allowed for smooth transfer of loaves in and out of the oven.

- Clay Ovens → Designed to retain heat and bake bread efficiently.

(1) Grinding Stones – Ancient Flour Milling – Hand-operated grinding stones, like this one, have been used for millennia to crush grains into flour. This method preserved essential nutrients, forming the foundation of early breadmaking traditions across civilizations.

(2) Wooden Paddles – The Baker’s Tool – Wooden paddles, or peels, have been an essential tool for bakers throughout history. Used to transfer loaves in and out of ovens, they ensured even baking and protected the integrity of the dough.

(3) Clay Ovens – Traditional Heat Retention – Clay ovens, dating back thousands of years, were designed to retain and distribute heat efficiently. Their construction allowed for consistent bread baking, a practice still used in many regions today.

💡 Egyptian bread, like aish baladi, remains a culinary bridge between past and present, connecting today’s bakers to an unbroken lineage.

Bread’s Journey Across Civilizations

As trade flourished, bread-making traditions spread across the Mediterranean and beyond, evolving with each new culture.

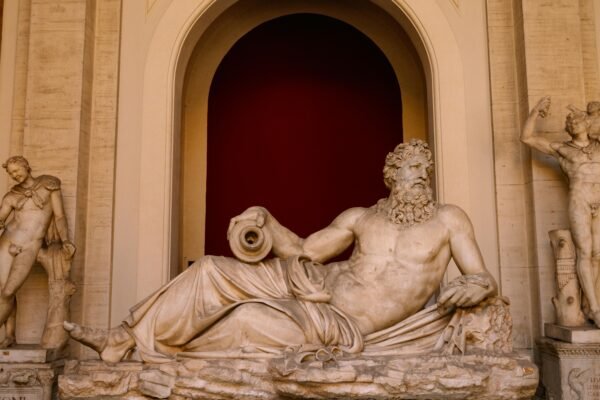

Greece: The Art and Ritual of Bread

- Bread was sacred, linked to Demeter, the goddess of agriculture.

- Greek bakers pioneered the use of olive oil, herbs, and honey in bread-making.

- Simigdalitis (σεμιδᾱλίτης), a fine wheat bread, became a delicacy among the elite.

(2) Demeter, Goddess of the Harvest – Bread held divine significance in Ancient Greece, closely tied to Demeter, the goddess of agriculture. Rituals and offerings of bread symbolized fertility, sustenance, and the cycle of life.

(2) Simigdalitis (σεμιδᾱλίτης) – The Bread of the Elite – A refined wheat bread enjoyed by Greek nobility, simigdalitis showcased the Mediterranean’s early mastery of fine bread-making, often paired with olive oil, honey, and herbs.

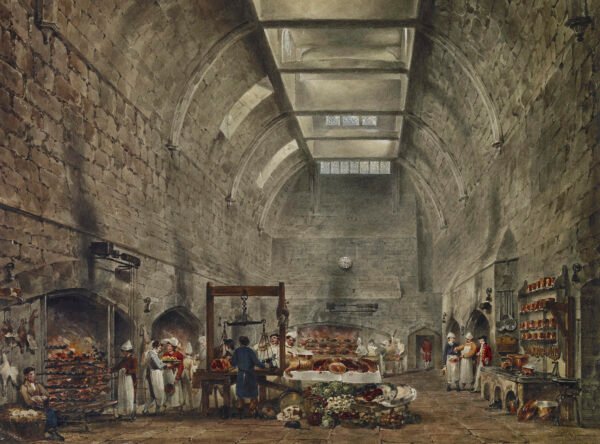

Rome: The First Bread Empire

- Romans industrialized baking, establishing the first professional bakeries during Emperor Trajan’s reign in the early 2nd century.

- Panis Quadratus, the iconic scored round loaf, became a common sight in Pompeii’s bakeries.

- Mass production ensured bread was no longer a luxury but a staple for all classes.

(1) Pompeii’s Bakery Fresco – This ancient depiction of a Roman bakery highlights the bustling bread trade, where professional bakers supplied markets and fed entire communities.

(2) Panis Quadratus – The Iconic Roman Loaf – A staple of Roman life, this distinctive round loaf with scored sections was found in the ruins of Pompeii’s bakeries, preserved under volcanic ash from Mount Vesuvius’ eruption in 79 CE.

During the medieval period, communal ovens became gathering places, and the type of bread one consumed signified social class—refined white bread for the wealthy, heartier whole-grain loaves for commoners.

💡 Bread was more than food—it was a marker of class, community, and ritual.

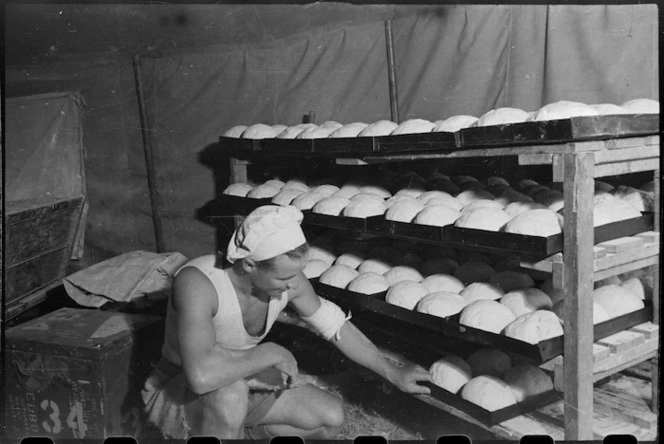

The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Modern Bread

The 19th century marked a turning point in bread production, transforming it from a craft to a science.

- Commercial Yeast → Standardized fermentation, increasing efficiency.

- Mechanical Mills → Roller technology produced flour on an unprecedented scale.

- Sliced Bread (1928) → Convenience reshaped consumer habits, leading to the phrase, “the best thing since sliced bread.”

(1) The Science of Yeast – A New Era of Baking – The development of commercial yeast in the 19th century revolutionized bread-making, ensuring consistent fermentation and expanding mass production.

(2) War-Time Bakeries – Feeding a Nation – Industrialized baking played a crucial role in wartime economies, supplying soldiers and civilians with reliable, standardized loaves.

(3) Sliced Bread – The Invention That Changed the Kitchen (1928) – When pre-sliced bread hit grocery shelves, it transformed consumer habits, setting a new standard for convenience and efficiency in food production.

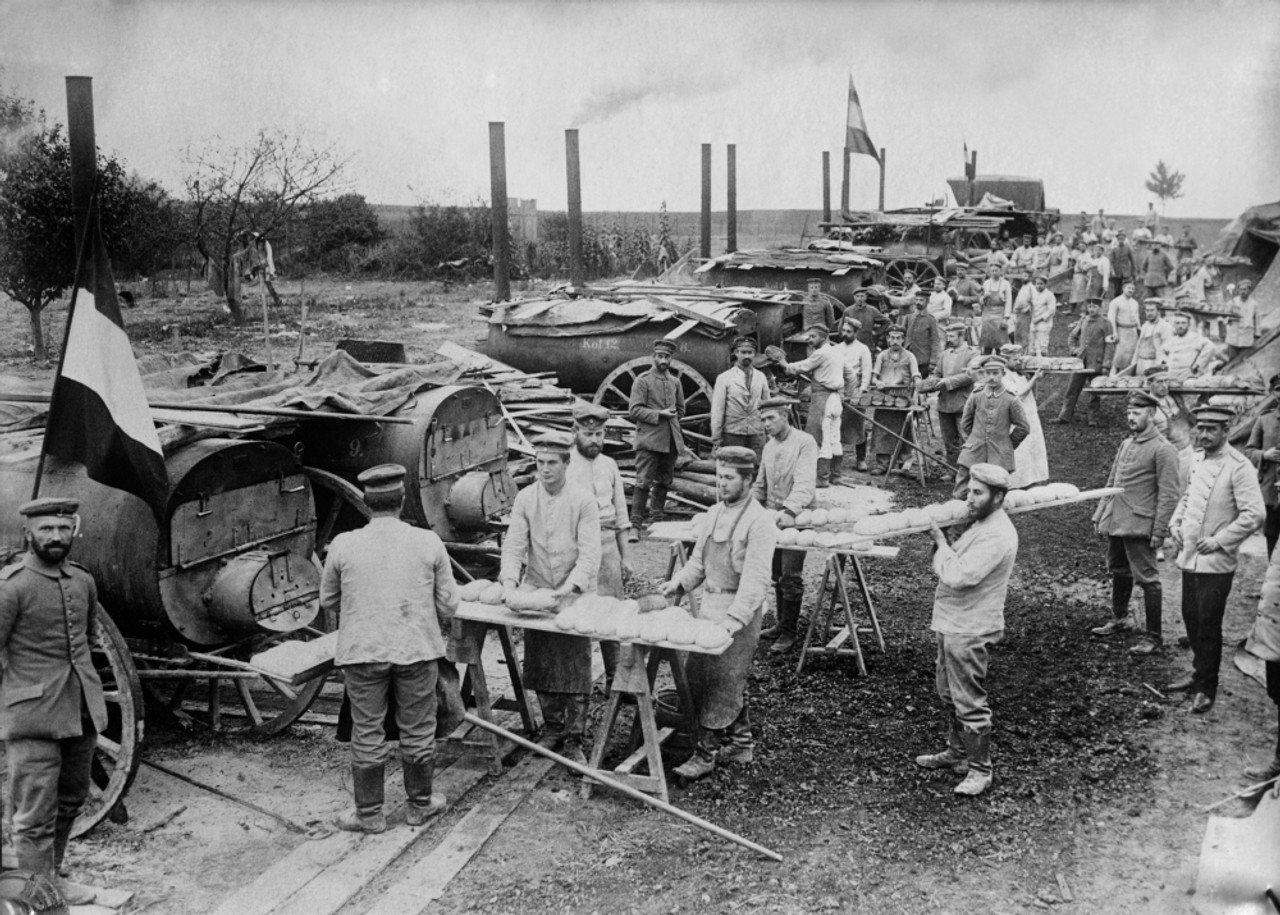

Wartime Bread: Innovation Under Scarcity

During World War II, governments introduced rationed “war bread,” made with alternative grains to conserve wheat supplies. In Britain, the National Loaf was fortified with vitamins to prevent malnutrition, proving that bread could be both an act of necessity and ingenuity.

(1) Tea and Morale – British Officers on the Front (1914) – Even amid war, British officers upheld the tradition of afternoon tea. The fine china, white linen, and silver teaspoons symbolized resilience, maintaining a sense of normalcy in the chaos of World War I.

(2) Feeding the Front – A German Field Bakery Near Ypres – Mobile field bakeries like this one sustained soldiers during World War I, producing thousands of loaves daily under battlefield conditions. Bread was not just sustenance—it was a vital part of wartime logistics and survival.

💡 War and industry shaped bread into the mass-produced staple we know today, but a return to tradition is reshaping its future.

The Artisanal Bread Renaissance

In response to industrialized bread production, bakers worldwide have revived ancient techniques, ushering in a new golden age of bread-making.

- Ancient Grains → Einkorn, teff, and spelt are making a comeback.

(1) Einkorn – The First Wheat – Cultivated over 10,000 years ago, einkorn is one of the earliest domesticated grains. Revered by ancient civilizations for its resilience and rich, nutty flavor, it remains a nutritious alternative to modern wheat.

(2) Teff – Ethiopia’s Supergrain – A staple in Ethiopian cuisine for over 3,000 years, teff is the foundation of injera, the region’s traditional sourdough flatbread. This tiny grain is packed with iron, protein, and fiber, making it a powerhouse of nutrition.

(3) Spelt – The Roman Empire’s Breadgrain – Once a staple in ancient Roman diets, spelt was prized for its sweet, nutty taste and digestibility. Valued for centuries across Europe, it is making a comeback in modern artisanal baking.

- Sourdough Revival → Naturally leavened breads are celebrated for their complex flavor and gut-friendly benefits.

- Hearth Baking → Wood-fired ovens offer depth and character unmatched by commercial baking methods.

(1) Sourdough Culture – An Ancient Craft – Fermentation has been at the heart of sourdough baking for millennia, with wild yeasts and lactic acid bacteria creating a uniquely tangy flavor and improved digestibility. This tradition, once a staple of early civilizations, is now celebrated for its gut-friendly benefits and deep culinary heritage.

(2) Wood-Fired Ovens – A Testament to Tradition – Hearth baking dates back to ancient times when communal ovens brought people together. The slow, radiant heat of wood-fired baking enhances the crust and flavor, preserving a method unchanged for centuries.

💡 Modern artisan bakers, like their Egyptian and Roman predecessors, recognize that bread is not just food—it is a craft, a ritual, and a connection to the past.

Cultural Significance and Global Bread Traditions

Across the world, bread remains a cornerstone of culinary identity.

- France → The crisp, airy baguette is a national icon.

- India → Naan, cooked in clay tandoors, is a staple of communal meals.

- Ethiopia → Injera, made from teff, serves as both bread and utensil.

- Japan → Shokupan, a pillowy milk bread, exemplifies Japanese baking precision.

(1) Baguette – France’s Culinary Emblem – With its crisp crust and airy interior, the baguette has been a symbol of French culture since the 18th century. Its production is so revered that UNESCO recognized it as an intangible cultural heritage in 2022.

(2) Naan – The Heart of Indian Tandoor Cooking – Originating from the Mughal era, naan is traditionally baked in clay tandoors, giving it a signature charred texture. This soft, pillowy bread has been a staple in Indian, Persian, and Central Asian cuisines for centuries.

(3) Injera – Ethiopia’s Fermented Staple – Dating back over 3,000 years, injera is a sourdough flatbread made from teff flour. More than just bread, it serves as both a plate and utensil, central to Ethiopian communal dining.

(4) Shokupan – Japan’s Pillowy Perfection – Introduced in the early 20th century, Shokupan was influenced by Western bread-making but perfected with Japanese precision. Its soft, slightly sweet texture makes it a breakfast staple and a key ingredient in delicate sandwiches like the katsu sando.

Bread in Religious and Social Traditions

Bread carries profound symbolic meaning across cultures:

- Jewish Challah → Represents unity and blessing.

- Christian Communion Bread → Symbolizes spiritual nourishment.

- Naan in Ramadan → Central to breaking the fast during Iftar.

(1) Challah – A Symbol of Tradition – This braided Jewish bread, often enriched with eggs and honey, is central to Shabbat and holiday meals, signifying unity, divine blessing, and the sanctity of communal gatherings.

(2) Sacramental Bread – Spiritual Nourishment – Used in Christian rituals such as the Eucharist, sacramental bread represents the body of Christ, embodying themes of sacrifice, renewal, and divine grace.

(3) Naan – A Staple of Ramadan – This soft, leavened flatbread is a key part of Iftar, the evening meal that breaks the fast during Ramadan, reinforcing hospitality and shared meals among families and communities.

💡 The act of breaking bread remains a universal gesture of hospitality and shared humanity.

The Timeless Legacy of Bread

From ancient hearths to contemporary bakeries, bread has endured as a fundamental part of civilization. It has adapted to wars, revolutions, and technological shifts, yet remains an ever-present force that brings people together.

At Palette Synthi™, we see bread as more than food—it is a bridge between past and present, an embodiment of both art and science, and a symbol of cultural exchange.

What’s your favorite type of bread? Do you have any family baking traditions?

Share your stories with #PaletteSynthi and celebrate the universal love of this timeless staple.

The story of bread is far from over. With every knead, every rise, and every shared meal, we continue an ancient legacy—one loaf at a time.